SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY

The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs

PAI 786 – Urban Policy

Professor Yinger

Case: Transforming Public Housing1

Under the leadership of Secretary Henry Cisneros, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, has spent the last two years exploring some ways to improve its cost-effectiveness by reorganizing programs and cutting spending. These plans took on an unanticipated urgency when, in response to the success of the Republicans’ tax cutting promises in the midterm election of 1994, President Clinton proposed a large “middle-class” tax cut of his own. Under current legislation, any tax cut must be “financed” by spending cuts, and the President promised to make whatever cuts were necessary. Indeed, some dramatic spending cuts, including the complete elimination of HUD, were contemplated by the Office of Management and Budget, OMB. Secretary Cisneros eventually convinced OMB that HUD had an important mission, but the price of keeping HUD was a program of extensive spending cuts there.

Secretary Cisneros’s proposals for the transformation of HUD were set out in a “Reinvention Blueprint” dated December 19, 1994. This document calls for some dramatic changes in HUD’s housing programs, including a consolidation of existing housing programs into a single housing certificate and a transformation in the support for public housing.

Housing Certificates

According to the HUD blueprint

“Reinvention would consolidate all current public housing, assisted housing and Section 8 rental assistance programs into one fund that provides Housing Certificates for Families and Individuals. The Housing Certificates would be the principal means by which the housing needs of low-income Americans–particularly vulnerable populations–are served.

Local and state governments, with a premium on metropolitan strategies, would allocate these flexible, portable Housing Certificates to low-income families, who would have maximum housing choice (‘the power to move’), and hold owners and managers of affordable housing to the discipline of the marketplace. The Certificates would, thereby, enable the Federal government to intervene on the demand side of the low-income housing market–as distinct from supporting the production of affordable housing units.

The current public and assisted housing system of tying subsidies to units rather than people would be phased out over the next three years. Like current recipients of Federal rental assistance, residents in public and assisted housing would ultimately be allowed to move to an apartment of their own choice. Federal support for substandard apartments would cease as residents are permitted–for the first time in 60 years–to make their own, informed housing choices.

Reinvention would be an exercise of responsible devolution. Localities and states would be required to design and implement plans that are consistent with national objectives (e.g. fair housing, income targeting, community-based participation, attention to special populations). Localities and states would also be held accountable for their actions; performance measures would be used to help both communities and the Federal government evaluate recipients on their real progress in meeting community investment and housing needs.”

Transforming Public Housing

“Public housing, which began 60 years ago as transitional housing for working people who had come upon hard times, has become a trap for the poorest of the poor rather than a launching pad for families trying to improve their lives. While it has worked in many communities, the rigid, top-down command and control system that has evolved over the years has left tens of thousands of people living in squalid conditions at a very high cost of wasted lives and federal dollars.

Our new approach to housing assistance for families and individuals has the following components:

* Give residents market choice in the search for affordable housing.

We would give public housing residents the choice to stay where they are or move to apartments in the private rental market. Operating and capital subsidies for housing authorities would be converted to Housing Certificates for Families and Individuals.

*Break the monopoly of housing authorities over federal housing resources.

We would require housing authorities to compete in the marketplace for low-income residents with other providers of affordable housing.

*Support families that are working to achieve self-sufficiency.

In the new Housing Certificate program, we will give greater preference to families who are working or are participating in “work-ready” and education programs.

* Change the landscape of distressed inner-city neighborhoods.

We would accelerate the demolition of uninhabitable and nonviable public housing projects. We would also end support for the development of “public housing” developments that are exclusively occupied by the very poor.

By the end of a three-year transition, HUD would get out of the direct funding of public housing by converting project-based public housing subsidies to tenant-based rental assistance. In the course of this transition, HUD would:

*deregulate thousands of well-performing housing authorities, allowing them to operate flexibly within a framework of national low-income housing goals and objectives and specific performance indicators;

*break up the worst, large, troubled housing authorities, divesting parts of their portfolios to non-profit owners and managers, including residents, where appropriate; and *demolish thousands of severely deteriorated units for which there is no market demand and relocate their residents using portable certificates.”

Analysis

The most dramatic feature of these HUD proposals is the complete elimination of project-based housing subsidies. This feature has brought both praise and condemnation for the HUD blueprint.

At one point, project-based subsidies, such as the Section 8, New Construction Program, were HUD’s main housing policy tool. However, extensive documentation of the relatively high cost of project-based subsidies, which rely on construction or rehabilitation, relative to certificate or voucher programs, which rely on existing housing, convinced many academics and policy makers that project-based subsidies were not cost-effective. Over the last twenty years or so, therefore, HUD has gradually shifted its emphasis from project-based subsidies to household-based subsidies, such as the Section 8, Existing Program. In fact, with the exception of a tiny amount of new public housing for the elderly, all project-based subsidies now paid by HUD are payments associated with projects built long ago; that is, virtually all new housing subsidies are household-based.

Nevertheless, the legacy of past construction programs remains. Some old public housing projects, built with little insulation and now with outmoded heating, plumbing, and electrical systems, are enormously expensive to maintain. Moreover, local housing managers are severely constrained by the federal rule that they cannot demolish any public housing units without replacing them, one-for-one, with new units. With no resources available for new construction, they must pour money into existing units, some of which clearly are not economical to maintain, or else be responsible for a decline in the number of housing units available in their city.

Some economists have called for the transformation of public housing subsidies into household-based subsidies. In 1993, for example, Professor Ed Olsen of the University of Virginia, a well-known expert on housing, wrote:

The federal government currently provides local housing authorities with $4.5 billion each year in operating and modernization subsidies for public housing. Housing authorities are inefficient providers of housing. We can eliminate this inefficiency and immediately empower all public housing tenants by using this money to offer them housing vouchers that can be used for renting or owning and for living in private or public housing. Since there are fewer than 1.5 million households in public housing, this will provide subsidies averaging slightly more than $3000 per year. Of course, the poorest households will get much larger vouchers, and eligible households with the highest incomes, smaller vouchers.

This will eliminate the monopoly power of public housing authorities with respect to tenants. At present, if a tenant leaves public housing, she loses her subsidy. Under the proposed scheme, housing authorities will be forced to compete with the private sector for tenants, albeit with the considerable advantage of having been given their projects.

Not all experts are so enthusiastic about household-based subsidies, however. Professor William Apgar, Jr. of Harvard University, another well-known housing analyst, argues that the cost advantages of certificates and vouchers have been exaggerated. Not only does the cost of housing construction vary widely from place to place, so that the cost of construction cannot be presumed always to be higher than the cost of certificates, but standard cost measures leave out spillovers to unsubsidized housing. “Just as vouchers may impose costs on nonparticipants by raising prices, construction programs may confer benefits on nonparticipants by lowering or holding in check market price increase,” says Apgar.

Moreover, the National League of Public Housing Authorities, NLPHA, has come out strongly against the HUD proposals. NLPHA argues that some households may gain by the increased choice that comes from the transformation of project-based to household-based subsidies, but that many households who wish to remain in their current housing project may be hurt if many of their neighbors decide to leave. After all, NLPHA points out, households who leave will take their certificates with them and these distressed projects will have even less support than the barely adequate support they now receive. Moreover, NLPHA points out that many public housing residents are content with the status quo. During the Bush Administration, for example, many public housing residents in cities with well-run housing authorities, including Syracuse, New York, objected strenuously to attempts by HUD Secretary Jack Kemp to sell public housing projects to the tenants. These residents will be even more concerned about portable certificates, NLPHA claims, than they were about resident ownership.

The Decision

You have just been hired as a staff analyst for the House of Representatives’ Committee on Banking and Urban Affairs. Congressman James Walsh of Syracuse, a senior Republican on this committee, has asked you to prepare an analysis of the housing proposals in the HUD blueprint. He wants to know the pros and cons of transforming existing project-based subsidies into household-based subsidies, and he wants your recommendation as to whether he should support the HUD proposals. If you support the HUD proposals in general but believe that they need modification, he wants to know what modifications are needed. If you do not support the HUD proposals, he wants a brief suggestion for alternative ways to save money in federal housing programs.

Congressman Walsh has asked you to present your analysis and recommendations at a forthcoming meeting of the Committee.

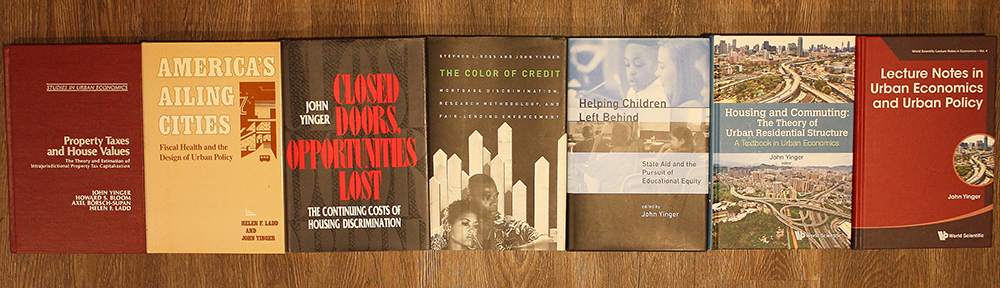

1This case was written by Professor John Yinger for the purposes of class discussion. In addition to HUD’s “Reinvention Blueprint,” it draws on “Fundamental Housing Policy Reform,” an unpublished manuscript by Professor Ed Olsen, University of Virginia, April 2, 1993, and “Which Housing Policy is Best?, by William C. Apgar, Housing Policy Debate, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1-32. The National League of Public Housing Authorities is a fictional organization invented for the purpose of this case.