NO AMERICANS SHOULD BE SECOND-CLASS CITIZENS

Prepared Statement by John Yinger(1)

Professor of Economics and Public Administration

Center for Policy Research, Eggers Hall

Syracuse University

Syracuse, NY 13244

(315) 443-3114

Before the House Committee on the Judiciary

Subcommittee on the Constitution

July 24, 2000

Introduction

The U.S. Constitution declares that only “natural born” citizens are eligible to be President. Because this provision denies naturalized citizens an important civil right, namely, the right to run for President, it turns them into second-class citizens. The constitutional amendment proposed in H. J. Res. 88 would extend presidential eligibility to naturalized citizens and would thereby ensure that all American citizens have exactly the same rights. This amendment therefore represents another important step in America’s longstanding quest to guarantee equal rights for all its citizens.

The right to run for President is obviously not as important for a person’s daily life as the right to free speech, the right to worship as one chooses, and the right to vote, among others. Nevertheless, this right has enormous symbolic power. Indeed, one could say that running for President is the ultimate symbol of equal opportunity. Regardless of income or ethnicity, parents of a natural born citizen can tell their child that he or she could grow up to be President. This is part of what makes the United States such a great country: You do not have to be born into wealth or social position to aspire to or even to attain the nation’s most powerful and prestigious job.

Because of its symbolic power, the right to run for President is important even for people who have no intention to run themselves. Imagine a high school civics class conducting a mock presidential election. Should the teacher tell naturalized citizens in the class that they are not allowed to run for president, just as they could not run in a real election? Or should the teacher simply point out that their candidacy in class would not carry over if the election were real? Either way, this situation undermines the standing of some citizens and is therefore an assault on the principle of equal rights.

Since the U.S. Constitution was passed, this nation has steadily expanded the coverage of constitutional rights and added new ones. The Bill of Rights and many other amendments to the Constitution provide examples of this process. So do the civil rights laws of the last few decades. Thus, eliminating the second-class citizenship of naturalized citizens would simply add another chapter to this long and honorable tradition. Indeed, given the symbolic importance of the Presidency, this step would make an abiding contribution to the equal-rights principle that is at the heart of the American democracy.

In the rest of this statement, I will bolster this argument by examining the origins of the presidential eligibility clause in the Constitution and by asking whether presidential eligibility is a suitable subject for a constitutional amendment.

The Origins of the Presidential Eligibility Clause in the U.S. Constitution

The historical record does not provide a full explanation for the origins of the requirement that the President be a “natural born” citizen. Nevertheless, some evidence about the origins of this requirement can be found in the records of the Constitutional Convention and elsewhere. In this section I summarize this evidence and discuss the implications of the historical record for H. J. Res. 88.(2)

Evidence from the Constitutional Convention

The clause restricting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens appeared in constitutional drafts near the end of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. The records of the Convention and other related material provide some evidence concerning the origins of this clause.

James Madison’s detailed notes on the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention reveal that the delegates were deeply concerned about foreign influence on the national government, and in particular on the President. At the beginning of the debate, they wanted the legislature to select the President, and they tried to limit foreign influence on the President by devising time-of-citizenship and other requirements for members of the legislature. Presidential qualifications as such were mentioned, but they received little attention at this stage in the debate. Ultimately, however, the delegates decided that a president elected by the legislature could not be insulated from foreign influence, no matter what eligibility requirements were placed on legislators, and they turned, instead, to the Electoral College.

The first draft of the Constitution that contained the Electoral College also was also the one that first contained the clause restricting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens.(3) This joint appearance of the Electoral College and the denial of presidential eligibility for naturalized citizens is somewhat ironic. After all, the switch to the Electoral College lowered the need for explicit presidential qualifications because it minimized the line of potential foreign influence running to the President through the Legislature. However, the long debate about eligibility requirements for legislators apparently left the Founders uncomfortable with prospect of eliminating all eligibility requirements in the process of presidential selection. As a result, they added the natural born citizen requirement even though it was no longer needed.

This addition may have been controversial. In fact, two of the most influential Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, argued against it, at least implicitly, earlier in the Convention by warning against any provision that created second-class citizens. Hamilton pointed out the “advantage of encouraging foreigners” to come to the United States. Then he said: “Persons in Europe of moderate fortune will be fond of coming here when they will be on a level with the first citizens.”(4) Madison agreed with Hamilton. “He wished to invite foreigners of merit & republican principles among us.”(5)

The records of the Convention do not contain any explanation for the restriction of presidential eligibility to natural born citizens, but this restriction might have been viewed as additional insurance against foreign influence. This interpretation is supported by a letter that John Jay wrote to George Washington, who was president of the Convention.(6) In this letter, dated July 25, 1787, Jay wrote:

Permit me to hint, whether it would not be wise & seasonable to provide a strong check to the admission of Foreigners into the administration of our national Government; and to declare expressly that the Command in chief of the american army shall not be given to, nor devolve on, any but a natural born Citizen (emphasis in the original).(7)

The meaning of this letter is not entirely clear. According to one historian, the first part of this letter was primarily directed at members of the legislative branch.(8) Moreover, the second part of the letter, where the expression “natural born” appears, probably was also not directed at the President; at that point Jay had no way of knowing that the Convention would ultimately make the President the commander-in-chief. Nevertheless, this letter may have had an impact on the delegates when the decision to merge these two positions was made. When Jay’s letter arrived, probably sometime before August 13, the Convention was not ready to deal with it.(9) But several weeks later, the idea of the Electoral College appeared and the President was made the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In this new context, the seed that Jay had planted appears to have born fruit.

Other Evidence

Evidence from the period right after the Constitutional Convention supports the view that the Electoral College was seen as the principal means of protecting the President from foreign and other undesirable influences, and that the presidential eligibility clause was, at most, a supplement to this objective. Two pieces of evidence are particularly instructive.

First, the issue of foreign influence is a key theme of the famous Federalist Papers, which were written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788.(10) The role of the presidential selection mechanism in limiting foreign influence is explicitly discussed by Hamilton in essay number 68.

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter, but chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils. How could they better gratify this, than by raising a creature of their own to the chief magistracy of the Union? But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have excluded from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office. No senator, representative, or other person holding a place of trust or profit under the United States, can be of the numbers of the electors.

Second, these issues were directly addressed in a statement by Charles Pinckney in the U.S. Senate in 1800. Pinckney had been a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and, on July 26, 1787, had been the first delegate to raise the issue of presidential qualifications in the debate. On March 25, 1800, Pinckney gave a detailed explanation for the Electoral College, emphasizing that the rules governing the Electoral College were designed so “as to make it impossible … for improper domestic, or, what is of much more consequence, foreign influence and gold to interfere.” The Founders “knew well,” he said that to give to the members of Congress a right to give votes in this election, or to decide upon them when given, was to destroy the independence of the Executive, and make him the creature of the Legislature. This therefore they have guarded against, and to insure experience and attachment to the country, they have determined that no man who is not a natural born citizen, or citizen at the adoption of the Constitution, of fourteen years residence, and thirty-five years of age, shall be eligible….(11)

Thus, in Hamilton’s view, the problem of foreign influence was solved by the Electoral College. He does not even mention the presidential eligibility clause. In contrast, Pinckney sees a role for the eligibility clause, but this role is clearly a secondary one. In particular, this clause promotes “attachment to the country” but is not needed to guard against “foreign influence and gold.”

Implications for H. J. Res. 88

A central example of the genius of the founding fathers was their creation of a process for electing the President that was insulated from, to use Hamilton’s words, “cabal, intrigue, and corruption,” foreign or otherwise. In this context, the restriction of presidential eligibility to natural born citizens appears to be a carryover from the debate, early in the Convention, about qualifications for legislators. Indeed, the Founder’s substantive arguments about the strengths of their constitutional protections against foreign influence all refer to the Electoral College, not to presidential eligibility. Pinckney asserts that limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens is a way to ensure “attachment to the country,” but he does not provide any justification for this conclusion. Moreover, Hamilton does not feel the need to mention the presidential eligibility clause at all in the Federalist Papers, and his most relevant comment on the issue in the Constitutional Convention was to warn against the creation of second-class citizens.

Two further points about this debate are particularly important. First, the potential for “cabal, intrigue, and corruption” is not just about foreign influence. This point is made very clearly in the above statements by Hamilton and Pinckney. The presidential election process has served this nation so well because it minimizes the role of these factors from whatever source. This process allows the American people, and the people they elect to the Electoral College, to select a President who will serve the nation’s interests. There is nothing special about the potential for foreign influence in this process and no need for a special provision to deal with foreign influence.

To put it another way, no Presidential candidate will be successful unless he (or she) can convince a majority of the American people that, among other things, he is “attached to the country,” not subject to foreign influence, not subject to subversive domestic influence, and not corrupt. Some presidential candidates face an extra burden to prove that they meet these conditions because of events in their past that make voters suspicious. Similarly, presidential candidates who are naturalized citizens would have to overcome suspicions associated with the circumstances of their birth and with their life before they became citizens. The clause limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens adds nothing of substance to this process.

Second, the distinction between natural born and naturalized citizens has no power whatsoever to identify people who might be subject to foreign influence, or any other kind of undesirable influence for that matter. To put it another way, being natural born is neither necessary nor sufficient for “attachment to the country.” Millions of naturalized citizens have served this country with honor and distinction in the government, in the military, and indeed in all walks of American life. Moreover, it is my impression that most of the cases of treason or governmental corruption that are discussed in newspapers or history books involve natural born Americans who turned against their country. It is simply preposterous to think that this nation can rule out or indeed even minimize the possibility of undesirable presidential candidates, regardless of how “undesirable” is defined, by limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens.

In short, there is no evidence that the clause limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens played an important role in the Founders’ scheme to protect the presidential selection process from foreign influence. Instead, this protection is provided by the Electoral College, and restricting eligibility to natural born citizens does not, and indeed logically cannot, provide any additional protection. This nation would do well to heed the warning against second-class citizens that was voiced by Hamilton and seconded by Madison. The presidential eligibility clause is an entirely pointless assault on the rights of naturalized citizens. It is time to stand up for the fundamental principle of equal rights for all citizens by eliminating this anachronistic provision.

Is Presidential Eligibility an Appropriate Subject for a Constitutional Amendment?

Another important issue is whether the denial of presidential eligibility to naturalized citizens is an appropriate subject for a constitutional amendment. Recently, a group called Citizens for the Constitution released a set of guidelines for constitutional amendments. According to its website, this group “is an action-oriented public education effort that is led by a non-partisan, blue-ribbon committee of former public officials, scholars, journalists, and other prominent Americans.”(12) Five of its guidelines refer to the substance of amendments; three others refer to the process by which amendments should be enacted. This section asks whether the amendment in H.J. Res. 88 fits the five substantive guidelines.

Guideline 1: Constitutional amendments should address matters of more than immediate concern that are likely to be recognized as of abiding importance by subsequent generations.

The principal of equal rights for all Americans is at the heart of our democracy. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights outline many rights that belong to all Americans. The Fourteenth Amendment ensures that no state can restrict the constitutional rights of any citizen. Overall, as pointed out by Citizens for the Constitution, seventeen of the twenty-seven amendments to the Constitution “either protect the rights of vulnerable individuals or extend the franchise to new groups.” By making all citizens eligible to be President, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 would be another step down this long and honorable path toward equal rights for all.

As discussed earlier, the right to run for President is not the most important right a person can have, but it is a right of enormous symbolic importance. An amendment declaring that all citizens can run for President (after reaching a certain age and spending a certain amount of time in the country) would forcefully declare this nation’s commitment to equal rights and equal opportunity, and would therefore be recognized “as of abiding importance by subsequent generations.”

Over 30 years ago a legal scholar, Charles Gordon, addressed the question of whether people born overseas to United States citizens could be called “natural born” citizens and hence be eligible to be President. After reviewing the legal history of the clause and subsequent legislation, Gordon answers this question in the affirmative. However, he also points out that the Supreme Court has never ruled on the issue and that “that the picture is clouded by elements of doubt.” This analysis leads him to the following conclusion:

It is unfortunate that doubts remain on an issue of such vital importance to many Americans. We live in a fluid and ever diminishing world. The interests of our nation and its people are constantly expanding and millions of Americans reside for short or long periods in foreign countries. They are there in pursuit of inspiration, enlightenment, profit, pleasure, repose or escape. All of these have a right to retain their status as American citizens while they live abroad. One can perceive no sound reason for shutting off aspiration to the Presidency for the children born to them while they are temporarily sojourning in foreign countries.(13)

With some editing, this eloquent statement can be expanded to include the case of all naturalized citizens.

We live in a fluid and ever diminishing world. The interests of our nation and its people are constantly expanding. Millions of Americans reside for short or long periods in foreign countries, where their children may be born, or build their families by adopting orphans born in a foreign country. Millions of other people come to the United States from other nations and become productive, loyal citizens. All of these people and their children should have full rights as American citizens. One can perceive no sound reason for shutting off aspiration to the Presidency for any American citizens, regardless of the path by which their citizenship was obtained.

Guideline 2: Constitutional amendments should not make our system less politically responsive except to the extent necessary to protect individual rights.

An amendment to ensure full American citizenship for naturalized citizens is a fortuitous case that both expands individual rights and makes our system more politically responsive by expanding the pool of people who can run for President. It does not limit any policy choices or create barriers to political debate.

Guideline 3: Constitutional amendments should be utilized only when there are significant practical or legal obstacles to the achievement of the same objectives by other means.

In many cases, a problem of unequal rights can be addressed through administrative procedures or legislation. This is not one of those cases. The exact distinction between “natural born” and “naturalized” citizens is not entirely clear.(14) However, it is clear that the Constitution makes many American citizens ineligible to be President. A person who was born overseas to citizens of another country, moves to the United States, and then becomes an American citizen is clearly included in this category. Administrative procedures and legislation cannot overrule a constitutional provision, so the only way to change this situation is with a constitutional amendment. To put it another way, the only way to ensure that all American citizens are eligible to be President is through a constitutional amendment, such as the one in H.J. Res 88.

Guideline 4: Constitutional amendments should not be adopted when they would damage the cohesiveness of constitutional doctrine as a whole.

As pointed out earlier, an amendment to make naturalized citizens eligible to be President is very much in keeping with the equal rights tradition in the U.S. Constitution and its amendments. This amendment would contribute to one key constitutional doctrine — equal rights for all citizens — and damage none.

Guideline 5: Constitutional amendments should embody enforceable, and not purely aspirational, guidelines.

In this case, the enforcement issue is straightforward; after all, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 simply eliminates a restriction on the rights of one group of citizens. All that needs to be done to enforce it is to allow any naturalized citizen who meets the age and residency requirements to run for President (and to assume the office if he or she wins the election!).

Conclusion

Overall, therefore, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 clearly meets all five of these guidelines. It addresses a matter of abiding importance, it makes our system of government more politically responsive, it does not have an administrative or legislative alternative, it reinforces the cohesiveness of constitutional doctrine as a whole, and it is easy to enforce.

Summary and Conclusion

The principle of equal rights for all citizens is one of the central themes of our democracy. The constitutional provision that limits presidential eligibility to natural born citizens is a direct assault on this principle, and it should be amended to make all citizens eligible to be President. The amendment in H. J. Res. 88 accomplishes this objective and indeed would significantly expand the rights of millions of Americans.

This limitation on presidential eligibility was of secondary concern to the Founders, who relied on presidential elections and on the Electoral College to limit foreign and other undesirable influence. Today, this limitation is simply an anachronism that undermines the principle of equal rights while serving no useful purpose.

The amendment in H. J. Res. 88 also unambiguously meets the thoughtful guidelines for constitutional amendments laid out by Citizens for the Constitution. Most importantly, this amendment would make an abiding contribution to the principle of equal rights.

All it takes to support H. J. Res. 88 is a belief in the principle of equal rights for all Americans. I hope everyone at this hearing joins me in supporting this vital principle. I hope you will all join me in supporting H. J. Res. 88.

__________________________

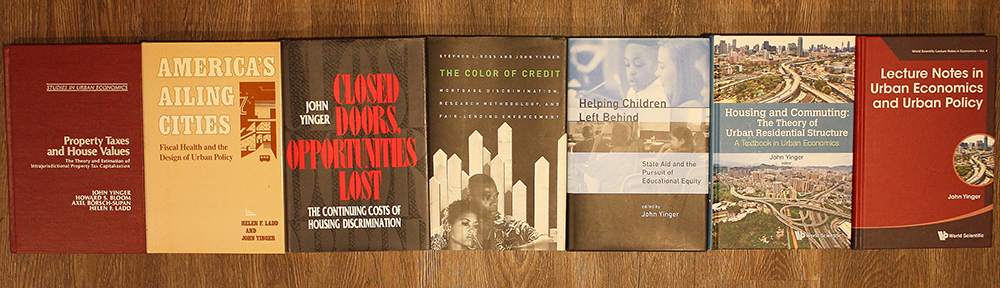

1.John Yinger is a scholar who specializes in civil rights, particularly discrimination in housing, and in American federalism, particularly education finance. He is also the proud father of two adoptive children, one of whom, even when old enough, will not be eligible to be President, at least not under current law.

2.For a detailed discussion of this evidence, see John Yinger, “The Origins and Interpretation of the Presidential Eligibility Clause in the U.S. Constitution: Why Did the Founding Fathers Want the President To Be a ‘Natural Born Citizen’ and What Does this Clause Mean for Foreign-Born Adoptees?”, http://www.maxwell.syr.edu/~jyinger/facfa.html.

3.The Founding Fathers did not rule out foreigners as such. In particular, they made anyone who was a citizen “at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution” eligible to be President. This phrase applied to thousands of foreign born citizens, including seven signers of the Constitution.

4.James Madison, Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1878 Reported by James Madison (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1966), p. 438.

5.Madison, op,. cit., p. 438.

6.John Jay was not a delegate to the Convention, but he was a well-known figure who had been President of the Continental Congress. Moreover, he would become an author, along with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, of some of the famous Federalist Papers, and he would later be appointed as the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. It seems reasonable to suppose that his letter carried some weight. See Richard B. Morris, Witnesses at the Creation: Hamilton, Madison, Jay and the Constitution (New York: Holt, Tinehart, and Winston, 1985).

7.Max Ferrand, editor, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Revised Edition, Volume III (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937), p. 61. This letter can be found at the Library of Congress web site: http://thomas.loc.gov. According to Charles Gordon, “Who Can Be President of the United States: The Unresolved Enigma,” Maryland Law Review, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Winter 1968), p. 5, this letter was sent to Washington and “probably to other delegates.”

8.Morris, op. cit., p. 191.

9.Actually, one delegate, Elbridge Gerry, was ready. On August 13, Gerrry argued that eligibility for the legislature should be “confined to Natives.” Morris (op. cit, p. 191) believes that Gerry’s concerns were stimulated by Jay’s letter. However, Gerry’s position did not catch on with the other delegates.

10.The Federalist Papers can be found on Library of Congress web site: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/const/fed/fedpapers.html.

11.“The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787” (Ferrand’s Records), CCLXXXVIII, Charles Pinckney in the United States Senate, March 28, 1800, p. 386-7, available at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:10:./temp/~ammem_jwJ2::.

12.This site is: http://www.citcon.org.

13.Gordon, op. cit., p. 32.

14.See Gordon, op. cit.