Myths Invoked to Defend Second-Class Citizenship for Naturalized Citizens

John Yinger(1)

Revised, August 24, 2000

On July 24, 2000, the House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on the Constitution, chaired by Representative Charles T. Canady, held a hearing on H. J. Res. 88. This joint resolution, which was introduced by Congressman Barney Frank, calls for a constitutional amendment to make naturalized citizens eligible to be President once they have been citizens for 20 years and reached the residency and minimum age requirements already specified in the Constitution. The text of this resolution can be found on the internet.(2)

At this hearing, henceforth called the Canady Hearing, Mr. Raimondo Delgado, a middle-school teacher from Representative Frank’s district who had convinced Representative Frank to introduce H. J. Res. 88, testified in favor of the amendment. So did I. Dr. Balint Vazsonyi, the head of a think tank, and Dr. Forrest McDonald, a history professor, testified against the amendment. The prepared statements submitted by Drs. Vazsonyi and McDonald, as well my own, can be found on the internet.(3)

The amendment proposed in H. J. Res 88 addresses an issue of equal rights. Because the U.S. Constitution denies naturalized citizens an important civil right, namely, the right to run for President, it turns them into second-class citizens. This amendment would extend presidential eligibility to naturalized citizens (once they have been citizens for 20 years and met other constitutional requirements) and would thereby ensure that all Americans have this important right. No citizens, naturalized and natural born, should be denied the right to have presidential aspirations.

The testimony against H. J. Res. 88 by Drs. Vazsonyi and McDonald was based entirely on a series of myths about naturalized citizens. The purpose of this paper is to state these myths and show why they reduce to nothing more than a bias against foreigners. The fact is that neither Drs. Vazsonyi and McDonald, nor anyone else at the hearing, made a single substantive argument against this amendment. The myths considered here are:

Myth Number 1: Naturalized citizens are inherently incapable of understanding American democracy or being fair;

Myth Number 2: Restricting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens helps the voters select a loyal President;

Myth Number 3: Allowing naturalized citizens to be eligible for the presidency would enable foreign powers to manipulate our presidential elections;

Myth Number 4: The Founding Fathers gave no reason to doubt the need for a limitation on presidential eligibility; and

Myth Number 5: The limitation on presidential eligibility is not a suitable subject for a constitutional amendment.

Myth Number 1

Naturalized Citizens are Inherently Incapable of Understanding American Democracy or Being Fair

Dr. Vazsonyi testified that people born in foreign countries are inherently incapable of understanding American democracy and therefore can be, as an entire class, ruled out as worthy of running for President. As he writes in his prepared statement for the Canady Hearing:

The people of this land are possessed of a unique brand of tolerance, a balanced temperament, and a natural goodwill toward the world. While such persons may be found everywhere, they constitute an overwhelming majority among Americans. One of the inexplicable miracles of America is the transformation that occurs within one generation, no matter how different the customs and mores of the new arrivals.

But it does require a generation….

Article II of the U.S. Constitution requires the President to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Mr. Chairman, it is an incontrovertible fact that the inhabitants of most countries are not only unfamiliar with what we call the Rule of Law, but find the concept virtually incomprehensible. Again, it is a miracle that so many immigrants are able to operate within the American system of laws, contracts, and agreements on a handshake. On the other hand, to expect that someone who did not grow up with any of that could be the guardian of our legal system is unrealistic.

In addition, liberty is not simply a blessing guaranteed by the Constitution, but an inner state of being, again separating Americans from most others. An overwhelming majority of immigrants arrive on these shores looking, as they had always done, to government as a source of benefits, and an authority to obey.

The strong claims in this passage are offered with no evidence whatsoever. As Representative Frank pointed out after Dr. Vazsonyi’s testimony, many other countries have histories of tolerance and the rule of law that are comparable to our own, and our history offers ample evidence to question the tolerance and goodwill toward the world of many American citizens. The fact that the United States is a unique country in many admirable ways does not imply that American citizens are qualitatively different from other people.

Indeed, many naturalized citizens have demonstrated a profound understanding of our system of government through their service in the government or in the military. Naturalized citizens have served in the cabinets of many Presidents, including the current one. They have been elected Senators and Congressmen and Governors. As discussed under myth number 4, they have even been elected President Pro Tempore of the Senate and Speaker of the House. They have faithfully executed the laws of the land as federal, state, and local officials. It is absurd to argue that naturalized citizens are inherently incapable of understanding the rule of law or of faithfully executing the law. Indeed, Dr. Vazsonyi’s statement is an insult to all of the naturalized citizens who have served their adopted country so well.

In fact, even Dr. Vazsonyi cannot bring himself to say that all naturalized citizens are unqualified to be President. He admits that people of “tolerance, a balanced temperament, and a natural goodwill toward the world…may be found everywhere” and that, even though he thinks it is a “miracle,” “many immigrants are able to operate within the American system of laws [and] contracts.” In response to a question from Representative Frank, Dr. Vazsonyi also acknowledged that his arguments do not apply to the tens of thousands of naturalized citizens who are adopted as enfants by natural born Americans.

In the end, one wonders what the problem is. Of course most naturalized citizens are not qualified to be President. Neither are most natural born citizens. As Representative Canady pointed out at the hearing, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 does not give naturalized citizens the right to be President. No citizen has that right. It only gives them the right to run for President. If a naturalized citizen could not convince the voters that he or she understood and would faithfully execute our laws, then he or she would not be elected President even if allowed to run.

A claim that naturalized citizens are inherently unqualified to be President should be recognized for what it is, namely an attack on foreigners, even if this claim hides behind seemingly patriotic statements about how wonderful and unique natural-born Americans are. According to the principle of equal rights that is at the core of our democracy, it is unfair and inappropriate to prejudge people on the basis of their race or ethnicity or national origin. This is just as true for the right to run for President as for any other right. The Constitution does not, and of course should not, bar American citizens from running for the Presidency because they belong to a particular racial or ethnic group, and it should not bar citizens who were born in another country.

Another version of this myth appears in Dr. McDonald’s prepared statement for the Canady Hearing. He believes there is a need for “safeguards” surrounding America’s powerful President. “The one area of presidential authority that is virtually unchecked and uncheckable (despite the War Powers Act and similar efforts) is the president’s power as commander in chief. Can that power be safely entrusted to a foreign-born citizen? John Jay didn’t think so; nor do I; not I suspect to the vast majority of Americans.” According to McDonald, here is the way a problem would likely arise:

A person comes to America from country “X” as a young man, takes out citizenship, becomes thoroughly Americanized, and is as loyal to his adopted country as can be. Nonetheless, in dealing with his original country he is bound to be influenced by his nativity, whether in the form of hostility of favoritism. Even should he prove able to rise above his prejudices and deal with the old country objectively, he would still be widely regarded as prejudiced, and the media would fan such suspicions. As commander in chief, it is not enough to be above reproach, one must be above the suspicion of reproach.

Let me cite a more tangible example, one closer to recent experience. We all know a number of Cuban-Americans. They are loyal to our country, now their country too. They are pillars of their communities and are more fiercely patriotic than most natural born Americans. And yet, as the recent to-do over Elian Gonzalez demonstrated, few of them are able to regard Cuba dispassionately or treat relations with Castro’s Cuba with equanimity. Suppose we had had a Cuban-born president in the White House at the time of the Gonzalez controversy. Would that president have been able to retain objectivity and, as importantly, any shred of credibility under the circumstances?

Here Dr. McDonald, like Dr. Vazsonyi, forgets that this amendment does not give naturalized citizens the right to be President, it only gives them the right to run for President. If voters believe that a Presidential candidate cannot “rise above his prejudices and deal with the old country objectively,” then they will not vote form him. And if voters believe that inevitable suspicions associated with a candidate’s nativity would undermine the credibility of his actions on important issues, then they also would not vote for him. Ironically, Dr. McDonald recognizes that the vast majority of voters would not want the commander-in-chief to be foreign-born, but he cannot bring himself to draw the obvious conclusion, namely, that voting provides a sufficient check on the commander-in-chief’s loyalty.

Inadvertently, perhaps, Dr. McDonald reveals what his argument is really about through his final example. Using the extreme behavior of some Cuban-Americans to attack the integrity of all Cuban-Americans is nothing more than an expression of prejudice against Cuban-Americans in particular and foreigners in general. Many Cuban-Americans maintained balanced views of the Gonzales case. Moreover, the extreme behavior in question was not limited to naturalized Cuban-American citizens, but also involved natural born citizens whose parents were born in Cuba and other natural-born citizens who simply had strong feelings about American policy toward Cuba. The strong negative reactions of voters across the country to Vice President Al Gore’s comments on this case, which were perceived as pandering to voters in Florida, also demonstrate that voters will not support candidates unless their positions on important issues are credible. It is ridiculous to think that presidential candidates who are naturalized citizens would be exempt from this requirement.

Myth Number 2

Restricting Presidential Eligibility to Natural Born Citizens Helps the Voters Select a Loyal President

A second myth is that if naturalized citizens were allowed to run for the Presidency, voters would be more likely to make a mistake in selecting a President. This myth was perpetuated by Dr. Forrest McDonald during his testimony at the Canady Hearing. In fact, Dr. McDonald began his testimony by saying that his argument against the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 could be summarized in two words: “Arnold Swarzenegger.” He declined to explain this summary but appeared to be claiming that if naturalized citizens were allowed to run for President, famous naturalized citizens who were unqualified to be President, such as (in his view) Mr. Swarzenegger, would certainly be elected.

Even without the amendment in H. J. Res. 88, voters already face the challenge of determining whether a famous natural born citizen who runs for President is qualified. Thanks to the efforts of the media, voters in this day and age have an enormous amount of information to help them make this decision. Dr. McDonald did not argue that the presidential election process is inherently flawed because some unqualified presidential candidates might succeed on the basis of fame acquired through some non-presidential career. Consequently, he must be claiming that there is something unique about naturalized citizens that gives them some kind of hypnotic power over the American electorate that natural born presidential candidates do not possess. This is patently absurd.

No Presidential candidate will be successful without convincing a majority of the American people that, among other things, he or she is qualified for the job and loyal to the nation. Some candidates face an extra burden to prove that they meet these conditions because of events in their past that make voters suspicious. Similarly, candidates who are naturalized would have to overcome suspicions associated with their life before they became citizens. If the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 were adopted and the voters believed that some candidate who was a naturalized citizens might be either unqualified or biased toward the country in which he was born, then they would not vote for him — just as they would not vote for a natural born citizen perceived to be either unqualified or biased toward a foreign country in which his parents were born.

Some people might respond to this point by saying that the American people can, in fact, be easily fooled. They might point to the election of some Presidents as evidence that the American people are quite capable of selecting someone who is unqualified to be President. Even if true, however, this argument does not prove that there is a need for a unique protection against the possibility that voters will select an unqualified naturalized citizen. A presidential candidate does not have to be naturalized to be unqualified, and candidates who are naturalized citizens would undoubtedly face an extra burden of proof with voters and therefore be even less likely to be elected, whether qualified or not, than natural born candidates.

In short, the claim that the Constitution must protect people against the possibility that voters will select an unqualified or disloyal naturalized citizen boils down, just like the first myth, to an irrational fear of foreigners. The foundation of our democracy is to let the voters decide, even if they might make a mistake. It makes no sense to sustain an exception to this principle in Presidential elections based on the fantasy that naturalized citizens would have some kind of unique hypnotic power over American voters.

Myth Number 3

Allowing Naturalized Citizens to be Eligible for the Presidency Would Enable Foreign Powers to Manipulate Our Presidential Elections

Some opponents of H. J. Res. 88 also have presented scenarios in which foreign powers manipulate naturalized citizens to undermine the United States. Dr. McDonald highlighted these scenarios in his testimony at the Canady Hearing. Here is what he says in his prepared statement:

Presidential candidates spend scores of millions of dollars; just consider the prospective influence of a few billion — a sum well within the means of a large number of countries any one of which, while quite unwilling to risk such a sum on a natural born American, might be eager to support a favorite son candidate, that is one who had been born and raised in their country….

Let us consider a few scenarios. Start with an extreme example. The espionage agencies of a number of countries, doubtless including the United States, have sometimes employed what in the spy novel is called an agent under deep cover. A young person is thoroughly trained and indoctrinated before being sent to an enemy country, where he or she becomes a citizen and an exemplar of respectable behavior. This goes on for years, even decades, until the parent agency determines that it is time to activate the agent. It is not difficult to imagine such a person obtaining an office of great trust. But a Senator is one of 100, and a Representative is one of 435. What check is there on the president who is one of one, except for the constitutional restriction?

A less dramatic version of this scenario was posed by Dr. Vazsonyi. In his prepared statement for the Canady Hearing, he writes:

While experience has shown that a naive-born Chief Executive is not necessarily immune to foreign influence, the odds are certainly more favorable if the president is an American plain and simple, who has never been, and is not at the time of taking office, anything else.

Representative Frank demolished this argument at the hearing. He pointed out that a foreign power that wished to disguise its actions would have a better chance of success if it used a natural born American in its diabolical scheme than if it used a naturalized American. After all, a natural born citizen would attract far less suspicion. Dr. McDonald’s claim that a foreign power would only lavish money on a favorite son candidate, not a natural born candidate, is simply not credible. A manipulative foreign power would be interested in results, not in sentimental attachment to people born within its borders. Moreover, Dr. Vazsonyi’s claim that some of our (natural born) presidents have been influenced by foreign powers undermines his position that we must rule out naturalized citizens to keep our country safe.

In fact, a foreign power could actually have it both ways even under the current constitutional provision. To continue in the spy novel vein initiated by Dr. McDonald, a foreign power would only have to identify one of its own citizens who was pregnant; send that woman on a trip to the United States to have the baby; bring that baby, who would be a natural born American, back to the foreign country for brainwashing; and then return him to the United States at least 14 years before his run for the Presidency (to meet the existing constitutional residency requirement). In other words, the clause restricting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens poses no barrier whatsoever to a foreign power who wants to subvert the American government. If follows that eliminating this clause cannot possibly boost the ability of a foreign power to install its hand-picked candidate as the American President.

I must confess that I find this spy novel game a bit far fetched. I do not for a minute think that foreign powers attempt to identify, brainwash, and then promote American presidential candidates. Even if they did, however, limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens does not provide the slightest bit of protection to the American public. Indeed, the argument that this provision does provide such protection is so illogical that it also must be seen as nothing more than anti-foreigner bias in disguise.

Finally, Dr. McDonald inadvertently provides some striking historical evidence against his own argument that restricting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens is necessary to prevent foreign conspiracies. In his prepared statement for the Canady Hearing, he says:

As an aside, the wisdom of the restriction and of the larger electoral system of which it was a part was soon borne out. In the presidential elections of 1796 and 1800 agents of Revolutionary France attempted by both overt and covert means to determine the outcome.

Dr. McDonald forgets, however, that the phrase limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens had no impact on the presidential elections of 1796 and 1800. After all, the presidential eligibility clause also (1) makes eligible all naturalized citizens at the time the Constitution was adopted, namely 1789, and (2) requires any presidential candidate, natural born or naturalized, to have been a resident of the United States for at least fourteen years. It follows that any person who was a naturalized citizen in 1789 and who met the fourteen-year residency requirement was eligible to run for President in either of these elections. Tens of thousands of naturalized citizens, many of them born in France, no doubt, fell into this category.(4)

Moreover, any person who came to the country and became naturalized after 1789 could not have met the fourteen-year residency requirement by 1800 and therefore would not have been eligible to run for President even if the Constitution had not included the restriction to natural born citizens. Hence, this restriction was irrelevant to these elections.(5)

These facts lead to a very different interpretation of the elections of 1796 and 1800 than the one provided by Dr. McDonald. These were elections in which naturalized citizens were allowed to run for president and in which a foreign power, France, actively tried to subvert the electoral outcome. Dr. McDonald attributes France’s failure to both the election process and the clause limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens. Since this clause was not yet in effect, however, France’s failure to subvert the election must be attributed to the election process alone. In fact, France’s efforts fell short even though naturalized citizens were eligible to be President, which is precisely the provision so feared by Drs. Vazsonyi and McDonald. This historical experience indicates that their fear is misplaced and that we need not be concerned about a return to this provision today.

Myth Number 4

The Founding Fathers Gave No Reason to Doubt the Need for a Limitation on Presidential Eligibility

A constitutional amendment cannot, and indeed should not, be passed unless it has a clear rationale. Moreover, the Constitution has served this nation so well that any proposed amendment inevitably faces a higher hurdle if it works against the expressed views of the Founding Fathers. The records of the Constitutional Convention do not explain why the Founders decided to limit presidential eligibility to natural born citizens. In fact, the version of the presidential eligibility clause in which this language was first used was accepted unanimously by the convention with no record of any debate or discussion.

Some opponents of H. J. Res. 88 interpret this silence in the written record as a good reason not to change this clause. We should leave well enough alone, they say. The clearest version of this argument is made by Dr. McDonald. His prepared statement for the Canady Hearing says that the language limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens “was adopted without a single dissenting voice. Nor did anyone speak in its support: its meaning and rationale went without saying.” A few pages later, he ends his statement as follows:

In conclusion let me say that on this as on other constitutional questions, we are best guided by the wisdom and prudence of the Founding Fathers. The amendment process is not to be taken lightly, nor should it be used for political or electioneering purposes. The structure created by the Constitution has stood the test of time and continues to stand as the truest foundation for our freedom.

In fact, however, the records from the Constitutional Convention and other historical documents indicate that the presidential eligibility clause was a compromise that did not by any means solve all the problems raised by the Founders.

First, the presidential eligibility clause itself admits that allowing naturalized citizens to be President is not such a bad thing. To be specific, this clause grants presidential eligibility to any “Citizen of the United States at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution.” As pointed out earlier (see footnote 4), this clause gave presidential eligibility to tens of thousands of naturalized citizens, included seven of the people who signed the Constitution.(6) If the Founders thought that naturalized citizens were inherently unqualified to be President or that naturalized citizens were inherently more likely than natural born citizens to be subject to foreign influence, then they would not have included this provision.

Although the records of the Constitutional Convention do not include any debate on this phrase in the presidential eligibility clause, the treatment of foreign-born citizens was considered during a discussion of qualifications for legislators on August 13, 1787. Gouverneur Morris moved that all current residents be exempted from the seven-year rule for eligibility to the House.(7) A lively debate ensued. For our purposes, the most telling comment in that debate was made by Nathaniel Gorham, who re-stated the principle of equal citizenship for all: “[W]hen foreigners are naturalized it wd seem as if they stand on equal footing with natives.”(8) Ultimately, Morris’s exemption was rejected, although it is certainly similar to the treatment of current citizens that later appeared in the presidential eligibility clause.

In short, the Founder’s ambivalence about limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens is right there in the presidential eligibility clause itself for anyone to see.

Second, in December 1798, the U.S. Senate took an action that testified to the Founders’ ambivalence, if not hostility, toward the natural born citizen requirement. To be specific, the Senate, which was full of men who had participated in the founding of the United States, elected a naturalized citizen, John Laurance of New York, to be its President Pro Tempore.(9) This action is significant because the clause in the Constitution giving presidential eligibility to people who were naturalized citizens when the Constitution was adopted applied to Laurance; he was born in England in 1750, sailed to America in 1767, and was admitted to the bar in 1772, all well before the adoption date of 1789. Moreover, the Presidential Succession Act of 1792 placed the President Pro Tempore second in the line of succession to the presidency.(10) For a brief period in 1798, therefore, a naturalized citizen, John Laurance, stood behind only Vice President Thomas Jefferson in the sequence of succession.(11)

Not surprisingly, Laurance had an impressive career. He served as a commissioned officer in the Revolutionary War, was a delegate to the Continental Congress, was elected to the House of Representatives in the first and second Congresses, was appointed a U.S. District Judge by George Washington, and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1796. Then, for one brief period in 1798, he was only two heartbeats away from the presidency.(12)

During this year, the so-called XYZ affair stirred up American patriotism, and tensions between the United States and both Great Britain and France were very high.(13) In the summer of 1798, the Senate responded by passing the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts, which authorized the President to deport “dangerous” aliens and imposed penalties for “malicious writing.”(14) Moreover, the year before William Blount, a natural born citizen, had been expelled from the Senate after “he was found guilty ‘of a high misdemeanor, entirely inconsistent with his public trust and duty as a Senator,’ because he had been active in a plan to incite the Creek and Cherokee Indians to aid the British in conquering the Spanish territory of West Florida.”(15) Despite the turbulence of the times, however, the Senate clearly believed that a man with a distinguished record of service to the United States should not be disqualified for the presidency simply because he was born in another country, even a country that was at odds with the United States.(16)

Third, several of the Founders warned against eligibility rules that would create second-class citizens. In the records of the Constitutional Convention, these warnings are made during a discussion of the potential qualifications for legislators. At that point in the Convention, it appeared as if the legislators would select the President, so presidential eligibility was in the back of the Founders’ minds during this discussion.

In any case, Alexander Hamilton first sounded the alarm. He recognized that there was a “possible danger” from foreign influence, but also said:

the advantage of encouraging foreigners was obvious & admitted. Persons in Europe of moderate fortunes will be fond of coming here when they will be on a level with the first citizens. He moved that the section be altered so as to require merely citizenship & inhabitancy. The right of determining the rule of naturalization will then leave a discretion to the Legislature on this subject which will answer every purpose.(17)

Thus, Hamilton explicitly declares that disqualifying people who are not “Natives” from public office will make them second-class citizens and discourage them from even coming to the United States.

If Hamilton alone had sounded this warning, it might be dismissed because Hamilton was, himself, born in a foreign country. However, James Madison, who was a natural born citizen and who is often called the father of the Constitution, seconded Hamilton’s motion. He also recognized the importance of avoiding second-class citizenship for immigrants. Specifically. “He wished to invite foreigners of merit & republican principles among us.”(18)

Fourth, several of the Founders argued against the specification of any qualifications in the Constitution, other than perhaps citizenship. The issue of presidential qualifications was first raised at the Constitutional Convention by Charles Pinckney and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney on July 26, 1787. Their motion to instruct a committee to come up with presidential and judicial qualifications in addition to qualifications for the legislature, was passed unanimously. Right after this motion passed, however, John Dickinson stated that he “was agst any recital of qualifications in the Constitution.”(19) The same point of view was expressed by Alexander Hamilton on August 13, when he said during the debate on legislative eligibility that he “was in general agst embarassing the Govt with minute restrictions.”(20) As noted earlier, Hamilton’s preferred approach was to limit eligibility requirements to “citizenship & inhabitancy.”

Fifth, the Founder’s ambivalence toward limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens is clearly revealed in statements made by Alexander Hamilton and Charles Pinckney after the Constitutional Convention was over.

Hamilton’s statement appears in an essay he wrote as part of the famous Federalist Papers. These papers were written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788 to convince New Yorkers to support the Constitution.(21) The role of the presidential selection mechanism in limiting foreign influence is explicitly discussed by Hamilton in essay number 68.

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter, but chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils. How could they better gratify this, than by raising a creature of their own to the chief magistracy of the Union? But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have excluded from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office. No senator, representative, or other person holding a place of trust or profit under the United States, can be of the numbers of the electors.

Pinckney’s statement was made to the U.S. Senate in 1800. As noted earlier, Pinckney was the first delegate (along with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney) to raise the issue of presidential qualifications at the Constitutional Convention. On March 25, 1800, then Senator Pinckney gave a detailed explanation for the Electoral College, emphasizing that the rules governing the Electoral College were designed so “as to make it impossible … for improper domestic, or, what is of much more consequence, foreign influence and gold to interfere.” The Founders “knew well,” he said

that to give to the members of Congress a right to give votes in this election, or to decide upon them when given, was to destroy the independence of the Executive, and make him the creature of the Legislature. This therefore they have guarded against, and to insure experience and attachment to the country, they have determined that no man who is not a natural born citizen, or citizen at the adoption of the Constitution, of fourteen years residence, and thirty-five years of age, shall be eligible….(22)

Thus, in Hamilton’s view, the problem of foreign influence was solved by the Electoral College. He does not even mention the presidential eligibility clause. As before, one might want to dismiss Hamilton’s neglect of the presidential eligibility clause as a reflection of his foreign birth. However, Pinckney’s remarks essentially second the Hamilton view. Although Pinckney sees a role for the eligibility clause, this role is clearly a secondary one. In particular, this clause promotes “attachment to the country” but is not needed to guard against “foreign influence and gold.”(23)

In short, the Founders made many arguments against limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens. The fact that they ultimately accepted this limitation as a compromise cannot make these arguments go away. Indeed, several of these arguments are clearly expressed in the historical record, and supporters of H. J. Res. 88 can find ample support for their position in the Founders’ own words and deeds.

Myth Number 5

The Limitation on Presidential Eligibility Is Not a Suitable Subject for a Constitutional Amendment

Finally, opponents of H. J. Res. 88 might argue that it is simply not a suitable subject for a constitutional amendment. Although Drs. Vazsonyi and McDonald did not put it quite this way, this argument appears to be implicit in their discussion. In fact, Dr. Vazsonyi began his prepared statement for the Canady Hearing saying that “Amendments to the Constitution are rarely necessary, almost never justified, and altogether inappropriate in the present political climate.” This statement would seem to imply that H. J. Res. 88 is not “necessary,” “justified,” or “appropriate.” Moreover, the concluding comment by Dr. McDonald, which was cited earlier, seems to imply that H. J. Res. 88 somehow takes the amendment process “lightly.”

As discussed in my prepared statement for the Canady Hearing, however, this point of view is just another myth. Recently, a group called Citizens for the Constitution released a set of guidelines for constitutional amendments. According to its website, this group “is an action-oriented public education effort that is led by a non-partisan, blue-ribbon committee of former public officials, scholars, journalists, and other prominent Americans.”(24) The five substantive guidelines proposed by this group set a very high standard for constitutional amendments. H. J. Res. 8 clearly meets this high standard.

Guideline 1: Constitutional amendments should address matters of more than immediate concern that are likely to be recognized as of abiding importance by subsequent generations.

The principal of equal rights for all Americans is at the heart of our democracy. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights outline many rights that belong to all Americans. The Fourteenth Amendment ensures that no state can restrict the constitutional rights of any citizen. Overall, as pointed out by Citizens for the Constitution, seventeen of the twenty-seven amendments to the Constitution “either protect the rights of vulnerable individuals or extend the franchise to new groups.” By making all citizens eligible to be President, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 would be another step down this long and honorable path toward equal rights for all.

As discussed in my prepared statement for the Canady Hearing, the right to run for President has enormous symbolic importance. In fact, the right to run for President can be seen as the ultimate symbol of equal opportunity, and naturalized citizens are second-class citizens because they are denied this right. All Americans should be concerned when some class of citizens is denied a basic right and the principle of equal rights is undermined. An amendment declaring that all citizens can run for President (after being a citizen for at least 20 years, reaching age 35 and spending at least 14 years in the country) would forcefully declare this nation’s commitment to equal rights and equal opportunity, and would therefore be recognized “as of abiding importance by subsequent generations.”

Guideline 2: Constitutional amendments should not make our system less politically responsive except to the extent necessary to protect individual rights.

An amendment to ensure full American citizenship for naturalized citizens is a fortuitous case that both expands individual rights and makes our system more politically responsive by expanding the pool of people who can run for President. It does not limit any policy choices or create barriers to political debate.

Guideline 3: Constitutional amendments should be utilized only when there are significant practical or legal obstacles to the achievement of the same objectives by other means.

According to the Constitution, a person who was born overseas to citizens of another country, moves to the United States, and then becomes an American citizen is unambiguously denied the right to run for President. Administrative procedures and legislation cannot overrule a constitutional provision, so the only way to change this situation is with a constitutional amendment. To put it another way, the only way to ensure that all American citizens are eligible to be President is through a constitutional amendment, such as the one in H.J. Res 88.

Guideline 4: Constitutional amendments should not be adopted when they would damage the cohesiveness of constitutional doctrine as a whole.

As pointed out earlier, an amendment to make naturalized citizens eligible to be President is very much in keeping with the equal rights tradition in the U.S. Constitution and its amendments. This amendment would contribute to one key constitutional doctrine — equal rights for all citizens — and damage none.

Guideline 5: Constitutional amendments should embody enforceable, and not purely aspirational, guidelines.

In this case, the enforcement issue is straightforward; after all, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 simply eliminates a restriction on the rights of one group of citizens. All that needs to be done to enforce it is to allow any naturalized citizen who meets the age and residency requirements to run for President (and to assume the office if he or she wins the election!).

Summary

Overall, therefore, the amendment in H. J. Res. 88 clearly meets all five of these guidelines. It addresses a matter of abiding importance, it makes our system of government more politically responsive, it does not have an administrative or legislative alternative, it reinforces the cohesiveness of constitutional doctrine as a whole, and it is easy to enforce. The denial of presidential eligibility to naturalized citizens is clearly a suitable subject for a constitutional amendment.

Conclusion

Thanks to the resolution submitted by Congressman Barney Frank and the hearing held by Congressman Charles T. Canady, the provision in the Constitution limiting presidential eligibility to natural born citizens is finally receiving the attention it deserves. The amendment in H. J. Res. 88 would expand the civil rights of millions of Americans and thereby help to sustain the equal rights principle that is so vital to the American democracy. It deserves a fair and open debate. This debate should not be governed by myths and distortions and anti-foreigner bias, but should instead focus on the constitutional principles raised by the amendment. I am looking forward to such a debate in the 107th Congress.

- John Yinger is a scholar who specializes in civil rights, particularly discrimination in housing, and in American federalism, particularly education finance. He is also the proud father of two adoptive children, one of whom, even when old enough, will not be eligible to be President, at least not under current law.

- The site is: http://thomas.loc.gov. Search for H. J. Res. 88 under “Bill Summary and Status” for the 106th Congress.

- The site is: http://www.house.gov/judiciary/2.htm. My testimony, along with an op-ed piece in support of H. J. Res. 88, can also be found on my web site: http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/jyinger/facfa.html.

- The total U.S. population was 3,929,214 in 1790 and 5,308,083 in 1800. Using the annual growth rate between those years, the population in 1789, the year the Constitution was adopted, was 3,812,786. According to Campbell J. Gibson and Emily Lennon (“Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-born Population of the United States: 1850-1990”, Population Division Working Paper No. 29, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C., February 1999, p. 1), “The 1850 decennial census was the first census in which data were collected on the nativity of the population.” This census reveals that in 1850, 9.678 percent of the population was foreign-born and 0.2581 percent of the population was born in France. The census of 1870 indicates that 33.8293 percent of the population consisted of men age 30 or older and that 64.1 percent of foreign-born men above age 21 were citizens. This is the earliest census that provides this information. (Men 30 or older in 1789 would be 37 or older in 1796 and therefore would meet the constitutional age requirement for the presidency.) Assuming that these shares applied in 1789, and that 75 percent of these men survived until the 1796 election, then 60,015 naturalized citizens were eligible to be President in the 1796 election, and 1,446 of these men were born in France. These rough estimates can also be applied to 1800 because naturalized citizens in the 24-28 age bracket in 1789 had by then reached the age required for presidential eligibility, whereas some of the naturalized citizens eligible in 1796 had died. This working paper and these population statistics can be found at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/pop-hc.html

- Strictly speaking, any person who moved to the United States before 1782 (1786) but who did not become a naturalized citizen until after 1789 would have been ineligible to run for President in the 1796 (1800) election because of the limitation to natural born citizens. However, this is obviously a small class of people. In addition, any person in this class who wanted to run for President would have had two years, from the end of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 (when the new rules were announced) to the adoption of the Constitution in 1789 (when the chance for a naturalized citizen to be eligible for the Presidency ended), to become naturalized if he had wanted to.

- The seven foreign-born signers were James Wilson, Robert Morris and Thomas Fitzsimons of Pennsylvania, Alexander Hamilton of New York, William Paterson of New Jersey, James McHenry of Maryland, and Pierce Butler of South Carolina. This list can be found at: http://www.nidlink.com /~bobhard/constit3.html). As it turns out, James McHenry is one of my ancestors, and my middle name is McHenry. Apparently, my interest in this issue is fruit from my family tree!

- Madison, op. cit., p. 439.

- Madison, op. cit., p. 440.

- At the time of the Laurance’s election, two senators (John Langdon of New Hampshire and Charles Pinckney of South Carolina) had been delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Moreover, all but three of the remaining senators had served in at least one of the following: the American Army during the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress, a state convention to ratify the U.S. Constitution, and the House of Representatives. Although there were 16 states at the time of Laurance’s election, it appears that only 17 senators were in attendance that day, just enough for a quorum, and that Laurance was elected on a voice vote. Those voting included Langdon, who had himself served three terms as President Pro Tempore, but not Pinckney. See the web sites of the U.S. Senate (http://www.senate.gov/learning/learn_history.html) and the Library of Congress (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsj.html). I am grateful to Betty K. Koed, Assistant Historian, U.S. Senate Historical Office, for helping me determine how many senators were present for this vote.

- Information on Laurance and on the Presidential Succession Act of 1792 comes from the U.S. Senate’s web site: http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=L000120 and

http://www.senate.gov/learning/brief_8.html. - In the late 1800s, the House of Representatives also selected two foreign-born Representatives to be Speaker of the House: Charles F. Crisp, born in England, was Speaker from 1891 to 1894, and David B. Henderson, born in Scotland, served from 1899 to 1903. However, the law of presidential succession that applied at that time did not give a high place to the Speaker (or, for that matter, to the President Pro Tempore of the Senate). The Speaker was not second on this list until 1947. See http://www.senate.gov/learning/brief_8.html; http://www.house.gov/house/Educat.html.

- In the early years of the U.S. Senate, the Vice President usually presided, and a President Pro Tempore was elected to preside only for periods when the Vice President was absent. Moreover, this post did not automatically go to the most senior member of the majority party, as it usually does today. In fact, before Laurance was elected, nine different men had served as President Pro Tempore, including three in the fifth Congress, and only two of these men had served more than one term. Laurance’s term lasted from December 6 to 27, 1798. See the U.S. Senate web site: http://www.senate.gov/learning/brief_8.html.

- The so-called XYZ affair involved an American mission to negotiate peace with France in which Tallyrand, the French foreign minister, attempted, unsuccessfully, to extract a bribe from the American delegation led by John Marshall, the future chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. This delegation had arrived in France in the fall of 1797, after their ship was boarded several times by the British navy while it passed through a British naval blockade of Amsterdam. However, news of their treatment by the French did not arrive in the United States until March, 1798. See Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer of a Nation (New York: Henry Holt, 1996).

- 14.The text of these acts can be found at The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/test.htm.

- 15.This quotation is from the biography of Blount on the U.S. Senate web site: http://www.senate/gov/learning/learn_history.html. Ironically, the possibility of impeaching Blount was discussed in the Senate the same day that Laurance was elected President Pro Tempore, December 6, 1798. See http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsjlink.html#anchor5. See also Richard A. Baker, “June 25, 1798: Compulsory Attendance” (on the passage of the Sedition Act) and “February 5, 1798: To Arrest an Impeached Senator” (on the expulsion of Blount), both available at: http://www.senate.gov/learning/min_2a.html.

- The Senate’s trust in Laurance can be seen in the official journal of the U.S. Senate. As part of his duties while President Pro Tempore, Laurance responded to a report by President John Adams on the fallout from the XYZ affair. His message to Adams, dated December 11, 1798, reads, in part:

We are of opinion with you, sir, that there has nothing yet been discovered in the conduct of France which can justify a relaxation of the means of defence adopted during the last session of Congress, the happy result of which is so strongly and generally marked. If the force by sea and land which the existing laws authorize should be judged inadequate to the public defence, we will perform the indispensable duty of bringing forward such other acts as will effectually call forth the resources and force of our country. A steady adherence to this wise and manly policy–a proper direction of the noble spirit of patriotism which has arisen in our country, and which ought to be cherished and invigorated by every branch of the government, will secure our liberty and independence against all open and secret attacks.The Senate apparently had no qualms allowing Laurance to participate actively in matters central to the defense of the nation! U.S, Senate journal is available through http://thomas.loc.gov. - Madison, op. cit., p. 438.

- Madison, op. cit., p. 438. More support came from James Wilson, who was foreign-born and whose own motion concerning legislative eligibility was under consideration at that time. He “cited Pennsylvania as proof of the advantages of emigration, and withdrew his motion in favor of Hamilton’s.” Madison, op. cit., p. 439. However, Hamilton’s motion was eventually rejected.

- Madison, op. cit., p. 374.

- Madison, op. cit., p. 438.

- The Federalist Papers can be found on Library of Congress web site: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/const/fed/fedpapers.html.

- “The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787” (Farrand’s Records), CCLXXXVIII, Charles Pinckney in the United States Senate, March 28, 1800, p. 386-7, available at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:10:./temp/~ammem_jwJ2

- As noted earlier, Pinckney missed a chance to act upon his views concerning the natural born citizen clause. The vote on John Laurance as President Pro Tempore took place on the first day of Pinckney’s term in the U. S. Senate, December 6, 1798, but Pinckney’s first appearance in the Senate came on February 16, 1799, when he presented his credentials. See: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsjlink.html#anchor5.

- This site is: http://www.citcon.org.

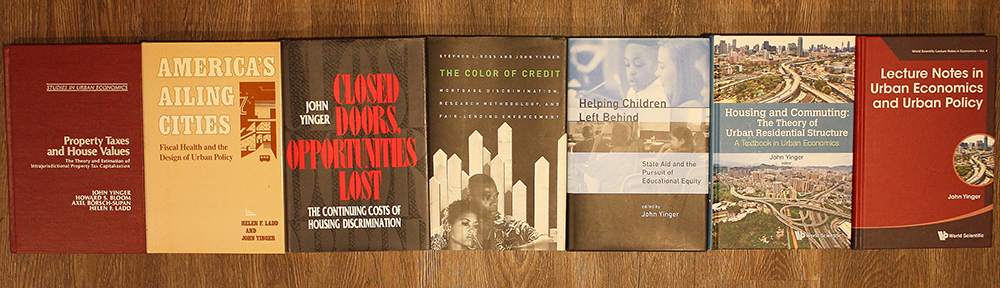

John Yinger is Trustee Professor of Public Administration and Economics; he also directs the Education Finance and Accountability Program, which promotes research, education, and debate about fundamental issues in the elementary and secondary school system in the U.S. Yinger studies racial and ethnic discrimination in housing and mortgage markets, as well as state and local public finance, particularly education. He has published widely in professional journals. His edited volume, Helping Children Left Behind: State Aid and the Pursuit of Educational Equity, appeared in 2004 and another book, The Color of Credit: Mortgage Discrimination, Research Methodology, and Fair Lending, Enforcement, co-authored with Stephen Ross, appeared in 2002. His 1995 book, Closed Doors, Opportunities Lost: The Continuing Costs of Housing Discrimination, won the 1995 Meyers Center Award for the Study of Human Rights in North America. He served as senior staff economist in the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, and taught at Harvard University and the University of Michigan. Yinger earned his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1974.