A Goal for Chairman Greenspan’s Last Term:

Effective Fair-Lending Enforcement

John Yinger*

August 22, 2004

The Syracuse Post Standard

Now that Allan Greenspan has been sworn in for another term as chairman of the Federal Reserve, it is time for him to get serious about the Fed’s fair lending responsibilities. These responsibilities include providing information about mortgage discrimination, developing standards for fair-lending enforcement, and detecting discrimination by the lenders under the Fed’s supervision.

Mr. Greenspan’s record on this issue is not very good. When he first became chairman of the Fed in 1987, the homeownership rate for non-Hispanic whites was 22.9 percentage points higher than the homeownership rate for blacks and 28.1 percentage points higher than the rate for Hispanics. By 2003, these gaps had risen to 26.6 and 28.7 percent, respectively. In 1995 (the earliest date with data comparable to the present), the conventional mortgage loan denial rate for blacks was 97 percent higher (and the rate for Hispanics 43 percent higher) than the loan denial rate for whites. By 2003, these differences had climbed to 108 percent for blacks and 58 percent for Hispanics.

These figures show the relative position of blacks and Hispanics in the mortgage market has not improved during Mr. Greenspan’s tenure at the Fed, but they do not prove that there is discrimination in mortgage lending. After all, they do not account for loan history and other factors that influence a loan applicant’s creditworthiness. The only study that accounts for these factors in a satisfactory way, a study sponsored by the Boston Fed, is based on data from 1990. This study found that blacks and Hispanics were 82 percent more likely to be turned down for a mortgage than were whites with the same credit qualifications—a clear sign of discrimination. I do not know whether mortgage discrimination persists at this level, but the recent growth of loan-approval and homeownership gaps certainly suggests that it has not yet gone away.

Independent scholars have no way to collect the data needed to update the Boston Fed study, and the Federal Reserve, which could easily collect the data, has refused to do so. As a result, there is no direct evidence on the extent of discrimination after 1990. Surely the first obligation of any fair-lending enforcement agency is to provide the public with information on the extent of the problem. The Fed under Allan Greenspan has failed to meet this responsibility.

The Fed under Greenspan has also fallen short in developing fair-lending enforcement procedures. Some background is needed to see why.

One type of discrimination is disparate treatment, which exists when different rules are used for people in different racial or ethnic groups. A lender who uses different standards to evaluate applications from blacks and whites is practicing disparate-treatment discrimination.

Our civil rights laws also prohibit disparate-impact discrimination, which exists when a business uses the same rules for everyone, but these rules place people in certain racial or ethnic groups at a disadvantage without any business justification. Suppose, for example, that homeowners in largely rental neighborhoods are no more likely to default on their mortgages than are homeowners in largely owner neighborhoods, all else equal, and that blacks are more likely than whites to want a house in largely rental neighborhood when they apply for a mortgage. Then any underwriting scheme giving positive weight to the homeownership rate in the neighborhood involves disparate-impact discrimination; this rate has no business purpose and puts blacks at a disadvantage.

The Fed’s fair-lending enforcement procedures focus on disparate-treatment discrimination in the underwriting decisions of large lenders. These procedures have detected flagrant discrimination by a few lenders and have led to settlements between these lenders and the Fed. Unfortunately, however, these procedures fail to find many other cases of disparate-treatment discrimination, such as discrimination by small lenders or discrimination in pre-application procedures. More importantly, these procedures make no attempt to uncover disparate-impact discrimination.

One might think that the rise of credit scoring and automated underwriting schemes will minimize discrimination because the loan-approval decisions are computerized and the lenders may not observe the customer’s racial or ethnic identity. Indeed, some mortgage applications are approved over the internet with no face-to-face contact between the applicant and the lender. In fact, however, this view ignores disparate-impact discrimination, which can exist even when a lender does not know the racial or ethnic group to which a customer belongs. Moreover, disparate-impact discrimination might even be magnified by recent developments, because it can be hidden in the weights placed on the factors in credit scoring or automated underwriting schemes. Instead of ignoring this possibility, the Fed should be pioneering methods to determine whether these schemes involve disparate-impact discrimination.

The Fed’s important role in monetary policy should not blind us to its fair-lending responsibilities. I call on Chairman Greenspan to implement effective fair-lending enforcement procedures and on Congress to hold Mr. Greenspan accountable for progress in fighting mortgage lending discrimination.

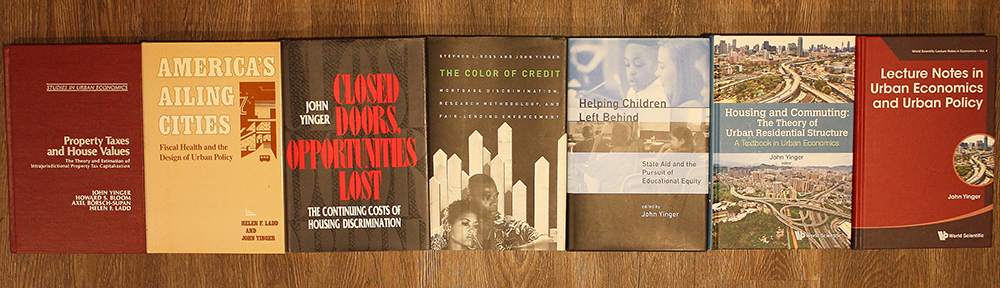

*John Yinger teaches at the Maxwell School at Syracuse University. He is the co-author (with Stephen Ross, University of Connecticut) of The Color of Credit: Mortgage Discrimination, Research Methodology, and Fair-lending Enforcement (MIT Press, 2002).