Proposition 209 is a Call to Action

John Yinger

J. Milton Yinger*

Now that a Federal Appeals Court has upheld Proposition 209, California’s anti-affirmative-action measure, our nation is in great danger of retreating from the fight for equal rights, a fight that is still vital to our future. We urge two steps to halt this retreat.

First, we must resist the temptation to define qualifications, for university admissions or employment, on the basis of simplistic criteria that inevitably favor advantaged groups. Standardized test scores, for example, are a poor predictor of wage rates or other measures of success. Exclusive or heavy reliance on these scores in an admissions or hiring process not only excludes many individuals who would do well by any standard, but also has a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged groups, particularly African Americans and Hispanics, whose average test scores are far below whites.

In the past, the University of California has admitted a large percentage of its students on the basis of standardized test scores and high school grades alone. If, in response to Proposition 209, the University of California were to base all its admissions solely on these two criteria, the impact on blacks and Hispanics would be devastating; such a policy would clearly have a disparate impact on these two groups, which, in other contexts, would be seen as a violation of our civil rights laws.

It has taken us decades to recognize the full dimensions of this disparate impact, and affirmative action policies have served as an invaluable buffer against over reliance on such easy-to-observe but ultimately unfair criteria. It would be tragic to retire this buffer without a replacement.

Thus we desperately need a national debate on ways to define “qualifications.” We need to find ways to broaden the criteria that universities use in admissions decisions and firms use in hiring decisions. Giving extra weight to applicants who come from low-income families, which is the most widely discussed criterion of this type, is a step in the right direction, but it is hardly the whole answer. Universities should also explore policies, for example, that give extra weight to applicants who have demonstrated a capacity to overcome disadvantages, such as a physical handicap, a poor school environment, or discrimination, or to applicants who are committed to serving people in disadvantaged communities. Policies along these lines are not being considered at the University of California.

Second, we must recognize that ethnic diversity plays a vital role in enriching our national culture and in breaking down stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Stereotypes and prejudice thrive in a world with little contact across ethnic lines. Discrimination, that is, disparate treatment of disadvantaged groups, is driven by prejudice. Thus continuing high levels of segregation in housing, schools, and employment, contribute to ethnic hatred and to discriminatory behavior.

We all pay a high price for this vicious cycle. Ethnic conflict pulls scarce resources away from other needs, and discrimination undermines the productivity of many citizens. In today’s competitive world economy, we do not have any citizens to waste. Moreover, prejudice and discrimination undermine the principles of equal treatment and equal opportunity that are so vital to our promise as a democratic nation.

Thus we also need a national debate on nondiscriminatory ways to promote diversity-in our neighborhoods, in our schools and universities, in our workplaces. In our judgment, programs to promote diversity are fundamentally different from group-based preferences. Consider an admission or hiring policy that gives extra weight to applicants who contribute to ethnic diversity in the classroom or workplace. This policy, unlike group-based preferences, states that membership in a certain group is neither necessary nor sufficient for a person to receive extra weight. Instead, extra weight depends on the context. At the University of California at Berkeley, for example, such a program would give extra weight to whites, blacks, and Hispanics, because the applicant pool is dominated by Asians.

Proposition 209 is a call to action, not a call to retreat. Let us as a nation reaffirm our commitment to enforcing anti-discrimination laws, to aggressively searching for qualified applicants from all ethnic groups, and to making extra efforts to ensure that all people, particularly those who belong to historically disadvantaged groups, have equal opportunities for success. We must not give in to the forces that separate us along ethnic lines. To fight prejudice and discrimination, we must instead embrace our diversity and find ways to bring our many ethnic groups together.

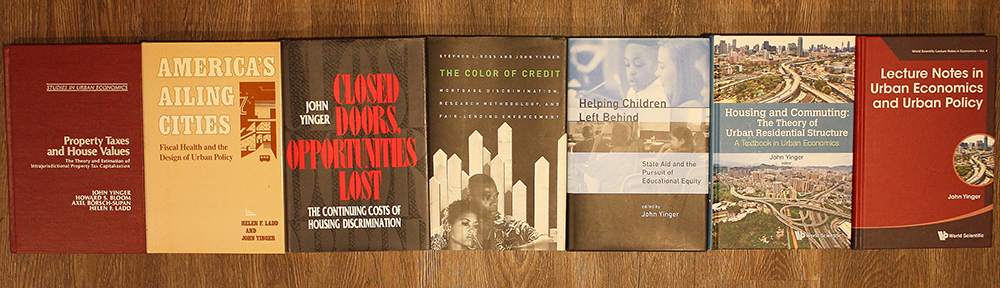

*John Yinger, Trustee Professor of Public Administration and Economics at The Maxwell School, Syracuse University, is the author of Closed Doors, Opportunities Lost: The Continuing Costs of Housing Discrimination (Russell Sage Foundation). J. Milton Yinger, Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Oberlin College, is the author of Ethnicity: Source of Strength? Source of Conflict? (SUNY Albany Press).