Reforming New York’s State Education Aid Dinosaur Finance

William Duncombe

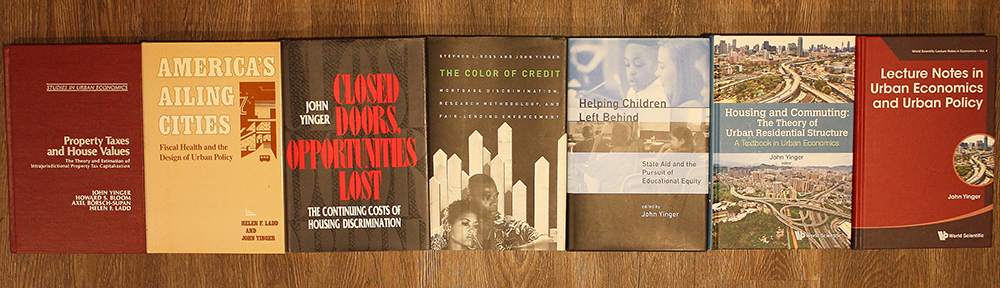

John Yinger*

The Herald Journal, Syracuse, NY (January 26, 2001)

Times Union, Albany, NY (January 28, 2001)

It’s been a remarkable month for education finance in New York State. A State Supreme Court judge found that the state’s school aid programs violated the state Constitution. Meanwhile, Governor Pataki, while vowing to appeal the court decision, declared that the state aid system was a “dinosaur” and proposed a $382 million increase in state educational aid focused on needy school districts. What is a citizen to make of all this?

First, some facts. School districts in New York State vary widely in both resources and costs. Property value per pupil is about $260,000 in New York City compared with $918,000 in the average New York City suburb, $184,000 in other large cities, and $276,000 in the rest of the state. Moreover, districts with high poverty have to pay more to attract the same quality teachers as rich districts and also must pay more for health and counseling, among other things, to obtain the same educational performance. We estimate that the per-pupil cost of education is 85 percent higher in New York City than in the average school district in the state. Costs in the other large cities are about 70 percent above the state average.

New York State spends more than $13 billion on state aid to education. To some degree, this aid is directed toward districts with relatively low resources or high costs, but this targeting is far too weak to offset existing disparities. For example, New York City receives less aid per pupil than the average district statewide. Another way to highlight existing inequity is to compare the current aid distribution with an aid program that costs the same amount but accounts for resource and cost disparities and ensures that all districts spend at least the current state-wide average spending per pupil. Compared to this more equitable system, current aid programs provide half as much aid for New York City, two-thirds as much aid for the other large city districts in the state, and three times as much aid for New York City’s suburbs.

Governor Pataki has proposed a small increase in state aid focused on “high-need” districts. This language seem consistent with the court’s mandate, but the proposed aid program would give New York City the same increase per pupil as the average district in the state — hardly a sign of an increased focus on needy districts. Governor Pataki also called for merging several existing aid programs but at the same time ruled out any change in aid distribution by declaring that no district should receive any less aid. Under his approach, any new assistance for needy districts must come from the $382 million in new aid funds.

Several issues must be considered in designing a new aid system that addresses existing school finance inequities.

First, these inequities are large and cannot be significantly lessened without either a much larger budget than proposed by the Governor or else significant redistribution of aid from rich to poor districts. It would take twice the amount proposed by the Governor just to bring New York City’s aid per pupil up to the state average. An aid program that accounts for the resource and cost differences across districts would cost far more, probably at least $6 billion.

Although these numbers may sound large, New York State has increased education aid by more than $3 billion over the last four years, with little impact on financing inequity. Morever, the State recently committed roughly $3 billion per year to STAR property tax exemptions, which exacerbate revenue disparities between city and suburban school districts.

Second, any solution must involve a major increase in aid to districts that, through no fault of their own, have relatively low resources or high costs. The state currently has a “Special Needs Aid” program that does a good job of directing aid toward high-cost districts. This aid program constitutes only 5 percent of the state aid budget, however, and Governor Pataki has proposed eliminating it as part of his aid-merger proposal. Moreover, high-need districts exist in all regions of the state, so regional cost adjustments, which largely differentiate between upstate and downstate, would do little to offset current cost disparities.

Third, any solution should require all districts, including the neediest, to raise a significant amount of revenue themselves. Districts that receive an increase in state aid tend to cut their property tax rate, and the school tax rate is now very low in some high-aid districts in New York State. Further aid increases would lead to property tax cuts, which would undermine the ability of aid to boost educational performance. The Governor’s proposals address this issue with a “maintenance of effort” provision. A better approach is the one used in most other states, namely, to require all districts to levy at least some minimum school property tax rate.

Higher funding for needy districts does not guarantee better student performance there, but it is equally true that even an efficiently managed district cannot expect to reach a high student performance level if it does not have the funds to attract good teachers and pay for its students’ special needs. The best approach is to make sure every district has the funding it needs to provide a quality education and then to help all districts identify best practices and hold them accountable for the results.

*William Duncombe and John Yinger are Professor of Public Administration and Professor of Economics and Public Administration, respectively, at Maxwell School, Syracuse University.

Address: Center for Policy Research, 426 Eggers Hall, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244.

E-mail: joyinger@syr.edu